A SERIES ABOUT HANTSPORT MARINERS

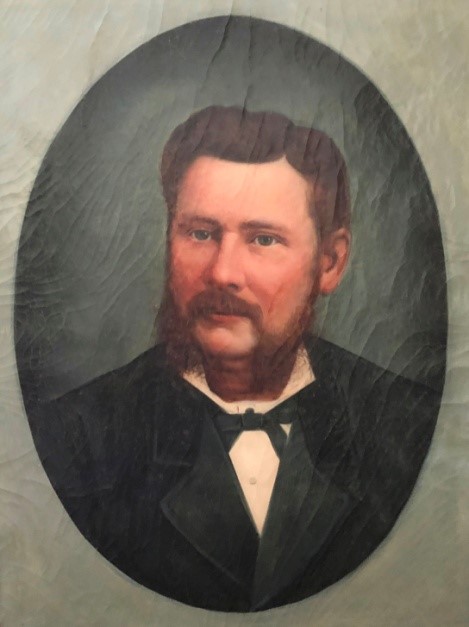

Captain William Folker

1837-1921

“His life, spent mainly at sea, sailing to every port in the world, with all its risks and dangers and adventures, abounded with interest, and were the incidents published in a book would be eagerly read.”

The above quotation from William Folker’s obituary was obviously written by someone familiar with his life story.

Ship logs, newspaper articles, historical records, and family scrapbooks all substantiate that Folker’s nearly forty years at sea were filled with extraordinary adventures. As a risk-taker he reaped astonishing rewards but in some scenarios suffered dire consequences.

William Folker was born on July 13th, 1837 in Snettisham, a village in Norfolk County, England; five miles from the North Sea. He took his first risk when he set sail as a cabin boy on a vessel bound for America from King’s Lynn, a nearby seaport. Boys aged 14–16 were often sent to sea by their parents to learn the skills necessary to becoming a master mariner. Some parents paid for this opportunity while others, fortunate enough to have a relative as an officer on a vessel, used their influence to secure a position for their sons. Serving meals and cleaning officers’ rooms were daily chores while scrubbing decks and taking turns at the helm in calm seas were also part of a cabin boy’s duties. In return for their services, the officers taught the young lads navigational skills, how to trim sails, tie knots and all the other skills required of a sailor. The boys played an important role relaying messages between the captain and crew, learning much from the orders they were communicating. The job was not always a pleasant one. Numerous articles chronicling the lives of cabin boys indicate that they were sometimes subjected to verbal, physical and even sexual abuse. In spite of those risks, the lure of adventure on the high seas and tales of exotic destinations enticed many young men to accept the job in hopes of one day becoming the master of their own vessel.

William Folker eventually rose through the ranks from that beginning as a cabin boy to achieve a high degree of success as a mariner. During his career he attained his Captain’s papers by age nineteen, a Master’s Certificate while in his forties, and became the owner or at least a shareholder of numerous ships.

Captains on sailing ships often led an isolated and lonely life and William Folker was no exception. Voyages were measured as the lapse of time from when a vessel left home until it returned, in some instances several years. The crew were mostly restricted to the forecastle and did not associate with officers. Many captains took their families with them to overcome their loneliness. How grateful Folker must have been when his wife and children were able to accompany him. When ships entered foreign ports they often lay at anchor for weeks or even months waiting for orders as to their next cargo and destination. On those occasions, visitation from vessel to vessel was a common practice for the captain and families. More often however they sailed without family. One entry in his logbook for the barque J. R. Hea simply reads: “My fourth Christmas at sea.”

Captain William Folker was not only a skilled seaman; he had an artistic side. He spent some of his long hours at sea painting and writing poetry. Samples of his talent remain to this day with his descendants. Records indicate he made 13 voyages around the world. It would have been wonderful reading, as the obituary author noted, if all of his adventures had been recorded.

Some of what is known is covered in the stories that follow.

New Beginnings in Hall’s Harbour, Nova Scotia

The ship carrying cabin boy Folker arrived in Halls Harbour, Nova Scotia circa 1853; quite likely for fresh water and supplies while en route to the United States. The quaint fishing village on the Bay of Fundy was, according to Eaton’s “History of Kings County”, a hub of commercial activity where merchants imported goods from foreign ports.

The sheltered harbour was also one of the first shipbuilding areas along the Bay of Fundy coast. It was here in Cornwallis Township that Folker’s fortunes in Nova Scotia began. He met the family of Tom and Rachael Parker, one of the early settlers. They had two sons and six daughters. Young Folker became smitten with Maria Almira Parker. Tom Parker’s sister Margaret had married Samuel Bucknam. Their son John, Almira’s first cousin, was a marine and naval architect and a partner of local ship builder David Eaton. The Eaton’s were one of the most influential families in the province at the time. Two other Cornwallis citizens played a role in Folker’s career. The first was J.B. North who moved in 1855 to Hantsport to commence ship construction. The second was Jedediah Newcomb, brother-in-law to Hantsport ship builder Ezra Churchill. These family and community connections would prove invaluable to the young Englishman’s future.

Almira Parker was almost five years younger than William but he was so infatuated with this young lady he took a risk in the name of love. When his ship weighed anchor Folker was not among the crew. One can only wonder what the captain thought of his cabin boy when he discovered the lad missing. Almira’s family took William in and once it became apparent that he saw a future with Captain Parker’s daughter, her father made his position clear. Family members say Captain Parker told William that “he couldn’t marry his daughter until he was successful in what he wanted to do in life”. Perhaps that was the motivation that prompted Almira’s suitor to become a captain over the next few years. The gamble of abandoning his ship paid off when, on Dec. 27th, 1857, he married this girl with whom he had fallen in love. Coincidently, their marriage took place on the anniversary of her parent’s wedding.

Folker’s sailing career, after arriving in Hall’s Harbour, can be traced through family memorabilia including log books of the vessels he commanded. One could surmise he gained his early nautical skills while sailing with Almira’s family or with the Bucknams. Records show he sailed on the Advance, built in Cornwallis Township in 1858 by David Eaton and on the schooner Florence, owned by J.B. North of Hantsport. He also commanded the J.R. Hea, another of David Eaton’s vessels.

In the early 1860’s Captain Folker and Almira moved to Berwick and then to Hantsport where they resided for the remainder of their lives. It seems only fitting that two of their sons would become ship captains, two daughters would marry ship captains, and two other sons would work in ship construction.

On board the brig Herald

In 1861 William Folker received his British Certificate, adding yet another credential to those he had already achieved. That year he took command of the Herald, a 231 ton brigantine built in Hantsport by J. B. North in 1854. At the helm of the Herald, he would soon undertake a major risk.

Folker had relieved long-time captain, John Toye, one of the Herald’s owners. Others with ownership shares included J. B. North, Capt. Kendal Holmes, Jedediah Newcomb, ship builder David Huntley and David R. DeWolf, a resident of New York. DeWolf, born in Kings County, was a ship broker.

On or about the 20th of May, 1861 the Herald arrived in Boston and was immediately chartered by William Williams of New York to go to Beaufort, North Carolina and load cargo for England. This was just five weeks after the start of the American Civil War. United States President Abraham Lincoln had declared a blockade of Confederate ports one month earlier. Lincoln’s proclamation created a 3,500 nautical mile barricade stretching from Virginia to Texas with the intent to prevent aid being given to enemies of the United States.

This was referred to as the Anaconda Plan. Although the United Kingdom remained neutral in the Civil War, the blockade of southern ports negatively impacted the textile industry in England as cotton exports became increasingly difficult. Running the blockade would become a lucrative business for captains who dared to risk it.

On May 22, Captain Folker cleared customs in Boston, declaring his destination as the Turk’s Islands in the Caribbean Sea. However, once the Herald left Boston harbour he set sail for Beaufort under ballast. Arriving at his destination on the morning of the 9th of June, Folker waited until the cover of darkness before entering the harbour. Insurgents had destroyed the lights at the harbour entrance making it less conspicuous to see vessels trying to gain entrance to the port at night but also making it more dangerous.

Over the next five weeks the Herald loaded cargo consisting of casks of turpentine, tar and rosin, as well as a shipment of tobacco and naval stores. Some of this cargo was owned by North Carolina exporters while other goods were consigned by merchants in London. The Herald also had one passenger, Nelson Dane Parmelee, who was travelling to Liverpool, England. On the morning of July 16th, Folker set sail for England but his journey was short-lived. On the high seas off Cape Hatteras the naval frigate St. Lawrence, a steamer, overtook the Herald. Initially the officer who boarded the Herald gave no indication that there had been any improprieties. He returned to his frigate but then returned again and asked Captain Folker to go with him and bring the ship’s registry papers and log book. Upon examination of these documents on the St. Lawrence, the Herald was then claimed to be in violation of the blockade and a prize crew was sent on board. The Herald was taken first to Hampton Roads, Virginia and later to Philadelphia to be adjudicated.

The following outlines Captain Folker’s arduous journey as he and the owners of the Herald and its cargo navigated the Civil War era justice system. Beginning with the initial adjudication by F.H. Stringham, the US Navy’s Commanding Officer of the Atlantic Blockading Squadron, next the District Court Trial, followed by the Circuit Court of Appeal and lastly the Supreme Court of the United States appeal; the process would take from July, 1861 to February, 1866.

The whereabouts of Capt. Folker and his crew after their brig was apprehended by Capt. Hugh Purviance of the frigate St. Lawrence is not fully clear. Records indicated Folker was detained on the Herald after it was taken to Hampton Roads. According to archivist Joe Keefe of the National Archives of Boston, captains were held accountable more so than the rest of the officers and crew. Whereas his crew were likely British subjects, Keefe stated they would “usually be paroled, and as part of their parole they would sign a document stating that they will no longer accept a crew position on any ship in rebellion against the US Government.” Once that was done, they would have been released to return home via ships departing for British Empire ports. In Captain Folker’s case, court proceedings indicate he remained in Philadelphia while adjudication of his ship and cargo took place. Family members recall being told he spent time in jail for his role in violating the blockade until after the Battle of Bull Run. As there were two battles by that name Folker could have been detained until either July 21, 1861 or August 30, 1862. It is very likely he was detained at least until the end of the District Court trial in February, 1862 and may very well have not been released until later that summer. Civil War records searched by this author show no evidence to support long-term imprisonment.

Adjudication

The adjudication in Philadelphia took place on August 6th, 1861. The Herald, assessed at $5,000 and the cargo, assessed at $57,708 were libelled as a “prize of war”. In today’s dollars those assessed values would be about $ 200,000 and $ 2.5 million respectively.

Political Intervention

Captain Folker gained an ally in his passenger, Nelson Parmelee, who went to New York and reported the capture of the Herald to the British Consul, Mr. Charles Kortright. Kortright immediately notified Lord Richard Lyons, British Ambassador to the United States, who intervened in Washington on behalf of the Herald. The following is a “New York Times” article that appeared on August 19th, 1861 reporting on the capture of the Herald after it was taken to Philadelphia.

“Lord Lyons, hearing of the capture at Washington, visited the Secretary of the Navy, and represented that the Herald belonged to British subjects in Nova Scotia, and demanded her release. A release was made out and sent to this city (Hampton Roads), but previous to its arrival the Herald was brought in, and the prize master had delivered her up to the United States authorities. The order of discharge was not, therefore, obeyed. Lord Lyons then made representations to the Secretary of State, Mr. (William) Seward, and another order was given directing that the vessel should be surrendered to her owners; but between the reception of the two orders, the papers of the brig were examined here, and it was found that the brig, though apparently belonging to British owners, was owned by Americans, and also that her intentions and orders were to force the blockade at Charleston. These facts were made known to Secretary Seward, and he immediately withdrew the order for her release, and directed that she should be subject to the decision of the prize court in Philadelphia.”

The “was owned by Americans” claim in this article became one of the contentious issues in this case. The authorities in the US felt the Herald was not a British owned property. David R. DeWolf, who lived in New York was a British subject as were the other owners, however two of the owners; DeWolf and Toye, had purchased shares in the Herald but had not registered them. Several affidavits were sworn by Folker, DeWolf and a Mr. Joseph Woodworth as to the fact that the Herald was a British owned ship. Joseph Woodworth was a Hantsport native who worked and lived in Philadelphia. He swore before the British Consul in Philadelphia that he was present at the launching of the Herald as was DeWolf. As far as the assertion that Capt. Folker was trying to get past the blockade at Charleston, that may have been an error on the part of the newspaper. It is known that the Herald was in Beaufort, North Carolina. Irrespective of these issues, the ruling by Secretary of State Seward prevented Captain Folker and the owners from recovering the vessel and the cargo. The owners of the cargo were, for the most part Southerners, and therefore enemies of the United States. If any cargo owners were from Union states, they could reasonably be seen as betraying their government.

The article in the “New York Times” references the correspondence between Flag Officer F.H. Stringham, the US Navy’s Commanding Officer of the Atlantic Blockading Squadron and the Secretary of the US Navy, Gideon Welles; as well as the correspondence between Lord Lyons, British Ambassador and Secretary of State William Seward. Flag Officer Stringham’s letter to Gideon Welles dated Aug. 1, 1861: “I have the honour to acknowledge receipt of letter from the Department July 30, containing copy of anonymous communication to honourable William H Seaward, New York, July 25; also letter of July 29, directing release of the British brig Herald, seized by the St. Lawrence. This vessel having sailed for Philadelphia, I forward a copy of your letter to Capt. Du Pont, who will carry it into effect. Respectfully, your obedient servant, S.H. Stringham.”

Over the next two months Capt. Folker filed appeals for the ship and cargo as did David DeWolf and William Williams.

District Court

The District Court, on February 8, 1862 condemned the vessel and the 655 casks of turpentine claimed by Folker, on behalf of North Carolina owners, and rejected the Master’s claim on behalf of the North Carolina shippers for the tobacco, as well as Williams’ claim for the barrels of turpentine, tar and rosin and the claims of David Huntley and Company for other items of cargo.

As for the vessel, the court said: “She should be condemned, both because her destination was falsified at the port of departure, and because her master, in the preparatory examination, made false statements, for the purpose of deception as to the ownership of the cargo.“

With respect to the 655 casks of turpentine, the court said: “The several shipments of turpentine which are not included in the claim of Mr. Williams have been claimed by the master, on behalf of the respective owners. They are parties who can have no standing in court as claimants. These claims are rejected, and the subjects of them condemned.”

With respect to the turpentine, tar, and rosin, claimed by Williams, the court said: “The claim of Mr. Williams for the tar and rosin and a portion of the spirits of turpentine cannot be allowed. But in rejecting it, I ought not to condemn the subjects of it. The bills of laden for this part of the cargo, described the shipper as an agent of the Liverpool consignees. This indicates an ownership in parties who, according to the rule of proceeding, are allowed a year to prosecute their claims.”

The court said, respecting the tobacco claimed by the Master on behalf of the North Carolina shippers: “The shipments of tobacco are according to the respective bills of laden, for the account of other parties in England, to whom the like delay should be extended. The claim in or disposed by the captain on behalf of other parties, who are probably the true owners of tobacco, is rejected.”

Circuit Court

The court records went on to state: “No claims having been in or disposed within the year allowed to such cases, by any neutral person for the turpentine, tar and rosin embraced in Williams’ claim, or for the tobacco embraced in the Master’s claim, the District Court finally condemned those subjects. The respective claimants having appealed to the Circuit Court from the sentences, that court, on October 18, 1862, did affirm the decrees and pronounce for the condemnation of the vessel and cargo. From this decree, the respective claimants were allowed to present appeals to this Court.”

Legal representatives, having failed to obtain the release of Captain Folker, the vessel and the return of the cargo then appealed the case to the Supreme Court of the United States. The following is an extract of the court findings.

SUPREME COURT

The Brig Herald and Cargo, William Folker, appellant — Vs.— The United States

Case # 70US 135, 2-5-66

Messrs. James Speed, Atty. Gen. and J. Hubley Ashton, assistant attorney general for the United States presented the case against the Herald and Captain Folker.

Representatives for the appellant’s were St. George T. Campbell, Beebe, Donahue and William Dean.

Damning Evidence

“It is contended on behalf of the United States, that the decree of the Circuit Court, condemning the vessel and cargo, should be affirmed, on the following grounds:

- That the vessel and cargo are liable to condemnation or breach of the blockade at Beaufort, North Carolina.

- That the vessel was liable to seizure on July 16, 1861 and was subject to condemnation for sailing to her primary destination at Beaufort, after the notification of the intended blockade of the Port of North Carolina, by the President’s proclamation of April 19, 1861, from a port of the United States for a port of North Carolina, independently of any question of the actual blockade of that port.

- That the vessel was subject to condemnation for sailing after said notification under a charter party, for a voyage from Boston to Liverpool, by way of Beaufort with the falsified clearance representing a fictitious destination from Boston to Turk’s Island.

- That the vessel was confiscated because of the conduct of the Master in knowingly making false statements as to the ownership of the cargo, in his preparatory examination.

- That the entire cargo of the Herald was the property of enemies of the United States and as such, subject to condemnation.

The brig Herald, a Nova Scotia built and originally a wholly Nova Scotia owned vessel, arrived at Boston on or about May 20, 1861. A state of war existed on that day between the United States and the insurgent people of certain states one of which was North Carolina. She carried a British register and a British flag. A portion 5/64 of her was owned, however, by Mr. David R. De Wolf, a merchant of New York. This interest, acquired in 1854, was never registered, nor was it evidenced by any proprietary document.”

The opinion of the Supreme Court – delivered by Mr. Chief Justice Chase

“The libel claimed the forfeiture of the brig and cargo as prize of war. The Master prayed restoration of the vessel in behalf of six alleged owners, all British subjects, of whom five were domiciled in Nova Scotia, and one in New York. He also prayed restitution of a part of the cargo, which consisted wholly of turpentine, tar, rosin, and tobacco products of North Carolina and Virginia, on behalf of the owners living in North Carolina; and of another part on behalf of persons believe to have an Interest, residing in New York, South Carolina, and in England. Restitution of the rest of the cargo was claimed by William Williams, a merchant, and a native and resident of New York. No proof of ownership of cargo was made, except on behalf of Williams and the parties living in North Carolina.

The principal question in this case is, was the Brig lawful prize? She was a neutral vessel, and the answer to the question must depend on her employment at the time of the capture.

Her master, under charter to Williams, had taken a clearance at Boston on 22 May, 1861, for Turk’s Island, while her real destination, concealed from the officers of the customs and from the crew, was Beaufort, in North Carolina. The excuse given by the master for false clearance in the concealment was his apprehension that his crew would not consent to a voyage to Beaufort, and his asserted intention to proceed to Turk’s Island, in case he should find Beaufort blockaded. Under the circumstances he sailed for Beaufort and, after laying on and off the entrance to the harbour about 24 hours, succeeded in getting in on 10 June. He saw, as he says, no blockading vessel at this time.

He remained at Beaufort taking in cargo, about a month, and then sailed for Liverpool.

The actual establishment of the effective blockade of the ports of North Carolina, in pursuance of the President’s proclamation of this 27th of April night 1861 was notified by Commodore Pendergast on 30 April; and is a matter of history that the notification, as well as the proclamation, became at once well-known throughout the country. It is impossible to believe that the Master of the Herald, at Boston, on 23 May, could have been ignorant of the facts so notorious. His conduct on arrival near Beaufort strongly indicates his apprehension of capture. The lights at the entrance of the harbour had been destroyed by the insurgents, and yet, though arriving in the morning of the ninth, he lay off and on some 20 miles south, all that day, and went in during the succeeding night.

The vessel, when once within the harbour, proceeded to take in a cargo. Some difficulties were encountered from the action of the rebel military authorities, and from the disturbed conditions of the country; but the laden was at length completed and the vessel sailed, as already stated.

During the month which he lapsed from arrival until departure, the effectiveness and stringency of the blockade were marginally increased. The Master, it is true, asserts that he still remained ignorant of its existence; but the evidence shows that it was the common topic of conversation in Beaufort and Morehead city; and he says himself that, while he was taking in cargo he saw from the tops of buildings, with a glass, a “man of war” off the harbour, once about three weeks, and the other about one week, before sailing. Another witness, a hand on the brig, says during the time the vessel was lying at Beaufort, he saw three different “man of war” off the harbour; and during the last two weeks he saw a “man of war” as often as once in three days. A letter from one of the shippers of the cargo, found on the brig, informs his correspondent that “a smoke had been seen off in the offing at one time, and it was thought to be one of the blockading squadron.”

It would be difficult to make more conclusive proof of the existence of the blockade, or of notice of the fact to the master of the captured vessel.

The cargo was shipped to be conveyed from the port by this brig, and it was in the same offense.

The facts of the case supply other grounds of condemnation. The shares of the vessel, owned in New York, and the portions of the cargo belonging to Williams, of New York, might be condemned for trading with the enemy; and other portions of the cargo might be condemned as enemies property; but it is enough that the vessel and cargo were equally involved in the attempt to violate the blockade. Both were rightfully captured. The decree must be affirmed.”

It had taken over four years for the case to be heard by the Supreme Court of the United States. That took place on January 4th, 1866 and the decision was delivered on February 5th, 1866. Their verdict in respect to the vessel upheld the 1862 Court decision and is recorded in the case file as noted below.

The Brig Herald and Cargo

Captured July 16, 1861; libeled August 6, 1861

Vessel appraised at——-$ 5,000.00

Cargo appraised at——- $57,708.50

Vessel condemned in the District Court March 18, 1862.

Cargo (part of) condemned in the District Court March 18, 1862

Cargo (residue of) condemned in the District Court October 7, 1862.

Appeal to Circuit Court from decree of condemnation of March 18, 1862

Appeal to Circuit Court from decree of condemnation of Oct. 7, 1862 and Oct. 17, 1862

Vessel and cargo condemned in the Circuit Court October 28, 1862

Gross proceeds of sale of vessel——— –$ 4,000

Gross proceeds of sale of cargo———- $ 67,444.18

$ 71,444.18

There was an increase of funds by investment of $17,818.96 in gold in Treasury notes of the United States —- $6459.37

Total $77,903.55 In today’s dollars that amounted to about $ 3 million.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Article that appeared in a Welch newspaper:

Taken from the supplement to the “Monmouthshire Merlin and South Wales Advertiser”, August 24, 1861

Running the blockade – Boston, August 1, 1861.

The British brig Herald, which was captured July 16, and taken to Philadelphia, for attempting to run the blockade, as reported yesterday, cleared from Boston May 27, ostensibly for Turks Island, but was then chartered by parties in New York, for Beaufort, North Carolina, with the intent to try the experiment of running the blockade.

It is well-known in this city, and in the city of New York, that other British vessels have left these ports within 30 days for Wilmington and other ports in North Carolina, to take cargoes for England and the British provinces.

The above article from Wales seems to validate that the blockade was indeed well known within the merchant shipping world. Captain William Folker’s claim of ignorance was unfortunately not believed. And unfortunately for Folker, the account of the events as provided by passenger Parmelee were also not believed. He stated he had been in Beaufort seven or eight days prior to the Herald’s departure and saw no sign of blockading ships while he was there or during the voyage until the St. Lawrence overtook them. He also stated that, to his knowledge, there were no postings in Beaufort of a blockade being in effect for that port.

The court had settled the issue but the consequences were dire for Captain Folker. His risk for a profitable reward failed. The time he was personally detained must have been very difficult for his family. Folker and the owners of the Herald along with the owners of the cargo paid a heavy price for being caught up in a civil war. Britain may have maintained a position of neutrality but history shows there was much animosity between the United States and the British Empire.

Side notes:

Attempts were made to discover what eventually became of the Herald. She had been registered in Windsor, Nova Scotia (Reg. # 37827) She remained in the British Ships registry from her launch year in 1854 until the United States Supreme Court ruling in 1866. It would appear when she was sold at auction as a “prize of war” she was re-registered as an American vessel. It is quite possible her name was changed as well.

American author Harry Castlemon, pen name for Charles Austin Fosdick of New York, a writer of historical fiction books used a British brig named Herald in one of his Civil War series published in 1891, entitled “Marcy the Blockade Runner”. The circumstances of the Herald were altered somewhat in his story aimed toward an audience of adolescent boys. The conversation concerning the Herald appears in Chapter 6: “Running the Blockade”.

This painting of the Herald was once part of an international crime exhibit.

In 2008 one of Canada’s most notorious art thieves visited Churchill House in Hantsport and walked out with two valuable paintings. Before being caught in 2013, John Mark Tillmann had amassed a collection of over 7,000 artifacts stolen from museums, libraries, galleries, antique shops and private homes all over the world. In his Fall River, Nova Scotia home investigators found two portraits of ships built by J.B. North & Sons and belonging to the Hantsport Memorial Community Centre. The 130 year old paintings were of the Hamburg and the brig Herald. The RCMP returned the paintings in 2014 and they are now on display in the McDade Heritage Centre. Tillmann, who had a lengthy criminal record, served only two years of a nine year sentence for these thefts. He died in December, 2018.

On board the barque J. R. Hea

How long it took William Folker to recover from his ordeal regarding the loss of the brig Herald and his imprisonment isn’t revealed in documents this author could discover but his sailing career certainly continued and his relationship with the owners of the Herald did not appear to have been jeopardized.

In 1868 Folker was captain of the J. R. Hea, a barque out of Windsor, N.S. of which he purchased shares in 1865. He had sailed to Bristol, England, and was about to experience drama on the high seas as the J. R. Hea crossed the Atlantic. It had been seven years since his capture off the coast of North Carolina. Once again he faced another high risk decision; one of life or death.

The Hea was one hundred miles off Cape Clear, a small island off County Cork, Ireland, bound for New York. The sea was running dangerously high. Wreckage was spotted; the crew visibly in trouble as the storm had shattered her main mast, toppling it but still secured to the deck because of its tackle. The tri- colored flag of France gave evidence as to her registry. Thirty-two men could be seen clinging for their lives to what was left of the splintered mast and spars. The vessel in distress was the brig Nautownier, a French fishing boat with crew out of Saint-Malo and Saint-Servan, two ports of close proximity in Brittany.

Sea rescues are perilous. In a raging sea; failure to carry one out successfully, could result in the loss of your own crew, putting your vessel and remaining crew in a precarious situation. Common practice in that era was for the captains to call for volunteers to man the long boats when attempting such a daring rescue. Rowing the boat through waves that could run as high as two-story house took not only strength, but a full measure of courage.

Captain Folker skillfully piloted his barque while the rescue crew lowered the long boat. Under his direction they made three arduous trips to and from the Nautownier, safely bringing aboard the thirty-two fishermen. Moments later the ill-fated Nautownier slipped beneath the ocean’s surface joining her captain who had washed overboard in the storm.

It likely would have been quite some time before the events of that day and the heroic rescue of the Brittany fishermen reached the fishermen’s families and French authorities. An article, published four decades later in the “Montreal Star”, June, 1912 stated this about Captain Folker’s risky decision: “he chanced death and stood by, saving every hand.” William Folker’s decisive action did not go unnoticed by the French government, under Emperor Napoleon III, who took steps to recognize his valor. The Emperor’s citation was published in “Mechanics’ Magazine” on July 16, 1869. It read: “The Emperor of the French has awarded a gold medal of the first class and a diploma to Captain Folker of the ship J. R. Hea of Windsor, Nova Scotia in acknowledgement of his humane services to the crew, thirty-two in number, of the French ship Nautownier, of St. Servan.”

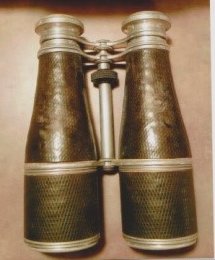

In addition to the medal and diploma, Captain Folker was also presented with a pair of platinum binoculars; all of which are in the hands of his descendants.

He reportedly received a sum of money as well. It is believed the presentation by Napoleon III took place in the Palace of Versailles. A model depicting the rescue, made by Captain William Folker, is on display in the McDade Heritage Centre in Hantsport; yet another example of this sea captain’s artistry.

Footnote: The vessel J. R. Hea is listed on the Wikipedia site for Ship Wrecks in 1875 as having been abandoned in the Atlantic Ocean on her way from Baltimore, Maryland to Queenstown, County of Cork, UK. Her crew was rescued by the American vessel Colorado. Almost ten years later a newspaper reported on September 25, 1884 that the brig Magenta, owned by Capt. William Folker was driven ashore in Chefoo, China where it had been carrying out coastal trade between Chefoo and Amoy. Unfortunately no other details were obtainable for either of these incidents. They underscore the risks taken by sailors in the “Age of Sail”.

**********

Little Risk — Great Reward

On board the barque Stadacona

In the fall of 1889, Captain William Folker was in command of the barque Stadacona (written as Staohcoma in some articles). After arriving in Pensacola, Florida he was doing business in the office of Thomas C. Waston when someone persuaded him to buy the last lottery ticket in the place. It was a ticket for the Louisiana State Lottery, a somewhat controversial lottery that supported the Charity Hospital of New Orleans to the tune of $40,000 annually. The lottery, which sold tickets all across America, had been operating for twenty-five years and was accused by many as being a corrupt organization. Francis T. Nicholas ran for Governor on an anti-lottery platform and was elected. The lottery’s charter was vetoed soon after Folker bought his ticket.

Last ticket for the last lottery! It definitely seemed like a “red sky at night” scenario for the captain. Folker’s ticket number was drawn as one of the prize winners on December 17th, returning him a delightful $15,000 for a ticket that cost him $1.00. It was a wonderful early Christmas present for the captain. Something like $600,000 in today’s dollars.

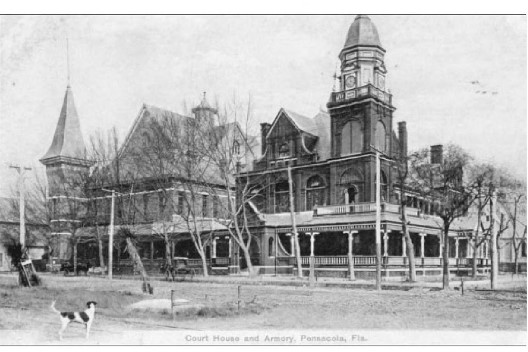

Folker was always considered by his family to be a generous and considerate man. Following his windfall he made an offer to the city of Pensacola. The city had constructed a new courthouse in 1883. Captain Folker noticed the bell tower did not have a clock and offered to make a substantial cash donation toward the purchase of one. His gesture, however, created controversy. Apparently some people were opposed to a clock being purchased with money that came, in part, from gambling. After all, the new governor had been elected because of his opposition to the lottery.

Approval was eventually given for the acceptance of the captain’s kind offer. Other civic minded citizens pitched in and the town soon had the $1,300 required to purchase the clock. The clock, manufactured by the E. Howard Clock Co. of Baltimore, considered at the time to be one the finest clock makers in the world, was safely installed on April 12th, 1890 along with a 1,500 pound McShane bell.

In 1925 the town fathers pondered replacing the clock with an electric one. The elderly caretaker of the bell, Mr. Lindenstruth, was outraged. “They can’t put up an electric clock — they mustn’t. They don’t have any works, any soul — they’re just a face with cords attached.” Lindenstruth had trudged up the winding tower steps each New Year’s Eve to make any necessary adjustment to ensure it struck exactly at midnight.

Bessie Lindenstruth, the clock caretaker’s daughter pleaded in a letter to the town authorities: “Let us hold fast to that which is good. Commissioners, spare that clock. It can be made to give perfect time. It has counted out only half of the three score and ten years of human life. It should be put into condition to count accurately a century of time.” Bessie’s letter saved the E. Howard clock and it remained ticking in the tower for another twelve years.

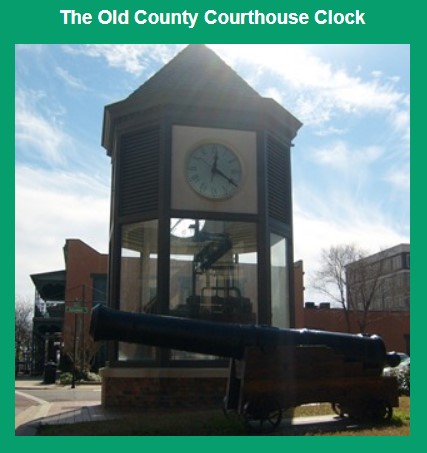

As time passed, the beautiful clock which Bessie Lindenstruth boasted would never wear out, if properly cared for, lived up to that expectation. Unfortunately the old Courthouse did not. The seat of justice for Escambia County was demolished in 1937. What would become of the clock Captain Folker played such a large role in obtaining for Pensacola? There were numerous suggestions for a new location but no decision was immediately made.

It took Bessie Lindenstruth’s intervention once again in 1938 to bring about an Act of Congress in Washington, supported by State Senators and members of the House of Representatives to save the historic timepiece. President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Act formally giving the clock to the Pensacola Historical Society. It would be up to that organization and its clock preservation society to find a new location. Sadly, no home was found. It stayed in storage in the basement of City Hall until 1964 when a town manager gave it to local businessman Francis Taylor who planned to put it outside his store. The clock preservation society learned of the town manager’s misguided decision and raised a ruckus. It took only a phone call for the manager’s decision to be overturned.

In the early 1980s the City Commissioners finally addressed the clock issue, agreeing to a new home in the Pensacola Square. One commissioner, who vowed to grow his beard until the clock was actually placed in its new home, finally got to shave in 1982.

Fittingly, the family of Captain William Folker were invited to the unveiling of the restored clock. A few members made the trip to Pensacola to honour the memory and benevolent gesture of their great-great-grandfather.

Cargo on board.

Captain Folker’s log books and ledgers reveal much in regards to his life at sea and the cargo he transported. One record shows he did business with Rev. Dr. Silas Rand, missionary to the Mi’kmaq.

Folker’s vessels carried, among many other types of cargo; fish, lumber, hides, apples, potatoes, turpentine, oil, coal, and gypsum to foreign ports while returning with textiles, spices, sugar, molasses, fruit, nuts, and crockery.

One cargo item that Folker brought from England was a crate of English sparrows. In the early 1850s canker worms were destroying massive numbers of linden trees in the eastern states. A decision was made to bring English sparrows to eat the larvae in an effort to save the trees. Over the next decade several organizations imported the birds to abate the canker worm issue. Other importers, immigrants from England, brought them to America simply because they missed seeing and hearing their song.

In 1857 Charles and Rupert Eaton introduced the English sparrow from the eastern U.S. to Lower Canard in the Cornwallis Township.

Captain Folker brought his shipment of English Sparrows to Chesapeake Bay in the latter part of the 1800s and may very well have been the one to have shipped them to the Eaton brothers.

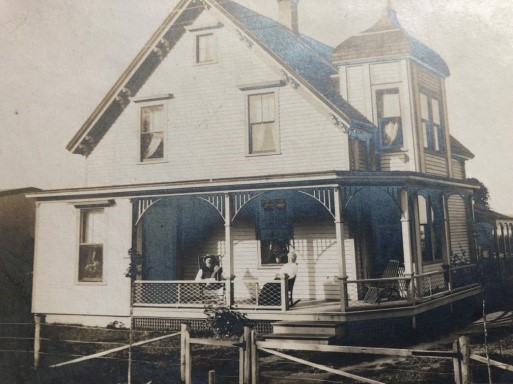

William Folker lived a long and prosperous life. From cabin boy to captain; his life at sea was indeed filled with much danger and many adventures. He and Almira remained in Hantsport in their retirement years; eventually moving to a home on Avon Street where they could feel the breeze of the incoming tide; a breeze that billowed his sails for more than five decades. Descendents of this seafaring couple continue to live in Hantsport overlooking the tidal waters of the Avon River.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the Folker family for stories, news clippings and photos. The model of the Nautownier rescue and the painting of the Herald are held by the Hantsport & Area Historical Society (McDade Heritage Centre). Appreciation is also extended to Dalhousie University Archives. Court proceedings were taken from the United States Supreme Court records. Information pertaining to consulate dispatches were taken from the “North America #8 Papers relating to the Blockade of the Confederate States, 1862” published in London by Harrison and Sons. Other information was found in internet publications. Appreciation is also extended to Judson Porter and Leland Harvie for their consultation and support.