A SERIES ABOUT HANTSPORT MARINERS

Robert “Bob” Carter Clayton

1916 – 1987

Wireless Operator

Bob Clayton was born in Saint John, N.B. His family later moved to Parker’s Cove, N.S. and in 1935 settled in Hantsport. He was the fourth of seven sons born to Capt. Delbert and Laura (Hudson) Clayton. The family moved to Hantsport, in part, because of Bob’s health. Bob had contracted tuberculosis and spent a year in the Kentville Sanatorium. Hantsport, being a seaport, brought employment opportunities for his father who was a tugboat captain.

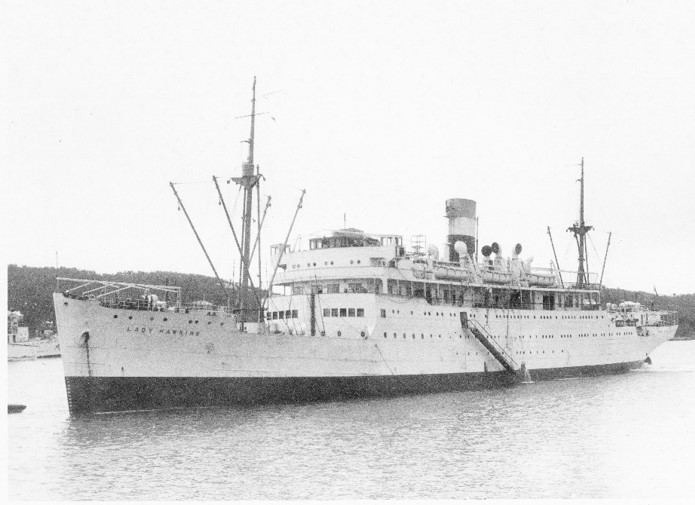

Clayton became engaged to Jennie Doris Ells in 1942. Doris, a 24 year old stenographer was a Willow Street neighbour but not the only lady Bob was infatuated with at the time. The other was Lady Hawkins, a magnificent luxury ocean liner owned by the Canadian National Steamship lines that called on ports in Montréal, Boston, Bermuda and other Caribbean islands. Officially the vessel was a Royal Mail Ship, but could carry cargo as well as passengers. Her home port was Halifax, N.S. RMS Lady Hawkins was one of five sister ships of the company’s line named in honour of the wives of British admirals who served in the Caribbean. They were among the first of the passenger liners where the officers and stewards wore white uniforms and the ship painted bright white. That all changed when war was declared; the ships were then painted grey.

Clayton was hired to serve as third wireless operator on the Lady Hawkins on August 1st, 1941. His unforgettable story with this “lady” began the evening of January 18th, 1942; two days after the liner sailed from Halifax, destined for Bermuda and then British Guiana. She was carrying approximately 213 passengers, 107 crew and 3,000 tons of cargo.

“infested waters”

These were war years. Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour Dec. 7th, 1941, the Americans entered the war. Germany responded to the American declaration of war by launching “Operation Drumbeat”; whereby twenty-five German U-boats were deployed from their base in the North Sea to seek prey in the North Atlantic. From January to August 1942, “Operation Drumbeat” was successful in sinking over 400 ships with 59 being Canadian Merchant ships. Needless to say, sailing on any merchant ship in the North Atlantic during this era was risky business, especially without a naval escort.

On that cold, dark evening in January the Lady Hawkins had a United States naval destroyer escorting her off the New York coast but after that she was on her own. A degree of anxiety swept over the ship as Captain Huntley Griffen ordered the lifeboats cleared away and readied. All windows were blackened with curtains and radio contact silenced. Many crew members who were normally quartered on the lower deck chose to sleep on the upper deck dining room floor. In a maneuver to lessen a torpedo strike the captain ordered his navigation officer to sail in a zigzag pattern.

As a wireless operator, twenty-five year old Clayton was well aware of the danger lurking below the surface. He had received radio messages indicating U-boat activity earlier in the day. He and the other two radio officers, or “sparks” as they were called in the merchant marine, were ordered to be ready to send mayday signals.

“in the crosshairs of a periscope”

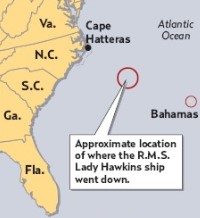

Clayton, who had just finished his shift in the radio room, had retired to his cabin not realizing they had already been detected by a U-boat hours earlier. 250 kms east of Cape Hatteras, off the coast of North Carolina, in total darkness, no one saw German U-boat 66 surfacing and preparing to launch its torpedoes.

Almost as soon as the U-boat’s searchlights illuminated the Lady Hawkins the first of two torpedoes struck their target. The first hit below the bridge; the second destroyed the engine room causing the oil-fired boilers to explode. The resulting damage destroyed three of the six lifeboats and knocked out all power to the ship. Within minutes the Lady Hawkins was ablaze and listing severely. Those trapped in the lower decks never stood a chance. The darkened gangways made it impossible to see. They were filling rapidly with inrushing water and smoke. The pungent smell of cordite filled the air.

Clayton raced to the radio room only to find it mangled and his fellow “sparks” dead. He tried to send an SOS signal but, with no power, it was in vain. There was nothing more Clayton could do. He made his way toward the lifeboat launching area and jumped into the frigid, oil slickened ocean and swam toward one of three lifeboats. Not a strong swimmer, he somehow managed to struggle to its side where he remained and assisted passengers and crew out of the icy water into the 30 foot boat. To his shock, a few minutes later, he heard a crewmember tell the chief officer there was no more room. Chief Petty officer Percy Kelly saw that it was Clayton. “He is a spark” shouted Kelly, “we need him.” Clayton was hauled aboard; making him the 76th person on a lifeboat certified to hold 63.

One of the most lingering memories of that pitch black night was the screams coming out of the darkness; people pleading to be rescued. Officer Kelly ordered the lifeboat to pull away knowing that when the Lady Hawkins went below the surface it could suck them under with it. Kelly later told journalists it was the most agonizing decision he had ever made. Those haunting voices disturbed Kelly and the others for the rest of their lives. From the time the first torpedo hit it was less than 30 minutes until the Lady Hawkins slipped beneath the surface. Moments later there was only the sound of silence. The survivors in lifeboat #2 huddled together and watched anxiously as the U-boat plied its search light over the floating debris. Then, it too slipped beneath the surface in search of another victim. The other two lifeboats were visible for only moments. They were never seen again, perhaps capsizing when the ship went down or in the violent storm that came upon them the next day.

“the struggle to survive”

With no distress signal given during the attack; the chance for rescue was bleak. For the remainder of that first night Officer Kelly ordered everyone to stay exactly where they were in fear that any movement might cause them to capsize. In the light of day they realized their predicament was a serious one. Being over capacity they were forced to take turns standing. Extra mouths to feed placed a further strain on the available rations which Kelly limited to half a biscuit and a sip of water for breakfast and supper and a mouthful of condensed milk for lunch. A bottle of brandy in the boat’s kit was reserved for illness. The only other beverage to share was a bottle of rum the bartender had taken before he jumped over the side.

Swells, as high as 10 meters, accompanied the storm that engulfed the lifeboat over the next 24 hours. The survivors bailed continuously to prevent their boat from swamping. Many of them were scantily clothed, and what clothing they wore was soaking wet. Salty skin, parched lips, dehydrated bodies and fuel ingested stomachs took its toll; four persons died over the next four days. The deceased were gently lowered over the side with a prayer, a sign of the cross and a hymn led by Mrs. Parkinson, a missionary. She had pleaded with Clayton to save her husband the night he assisted her into the lifeboat. Her husband drifted off in the darkness and was never heard from again.

“a moment of levity”

After the storm calmed on the second day they discovered a passenger who had, up until that time, remained unseen by most and mysteriously silent. It was two-year-old Janet Johnson who, amazingly, had been calmly cradled in the arms of her mother. Kelly cleared space in a storage hatch for the mother and child. Janet developed a fever and was given brandy. It proved helpful but was too much alcohol for a toddler. She became giddy. The giggling little girl brought smiles and bursts of laughter to the otherwise somber group.

Bob Clayton and others shared their milk ration with Janet and when a milk can was emptied they swished it with water and gave it to her as well.

The lifeboat was equipped with a pole for a mast, a sail, and an oar for a rudder. Aside from the meagre food rations, the only other aide was a flashlight to use as a signaling device. Officer Kelly set a westward course toward the US coast; one that would hopefully drift them into shipping lanes.

For four days they bailed water continuously while enduring the harsh elements. At times some of the survivors became delirious, babbling incessantly. Miraculously, a ship was sighted on the fifth night. Clayton grabbed the flashlight and flashed an SOS Morse code of distress. The signal was ignored! No response! Clayton then flashed the signal again using the sail of their lifeboat to reflect his message. Only then did the ship’s captain realize it was a true distress call. The steamship Coamo, (formerly commanded by Hantsport captain Fred Folker) on its regular run from New York to Puerto Rico came to the rescue. Later, they discovered that the captain thought the distress signal was a submarine trying to trick them. Tragically, a fifth person died as he slipped trying to step from the lifeboat onto the Coamo’s rope ladder. The Lady Hawkins’s survivors were taken to Puerto Rico where they contacted love ones to inform them of their rescue.

The news of Bob’s rescue was met with tremendous joy and relief in the Ells house. Doris, at the time, was Bob’s fiancée. She had been inconsolable since the news of the sinking of the Lady Hawkins reached Hantsport.

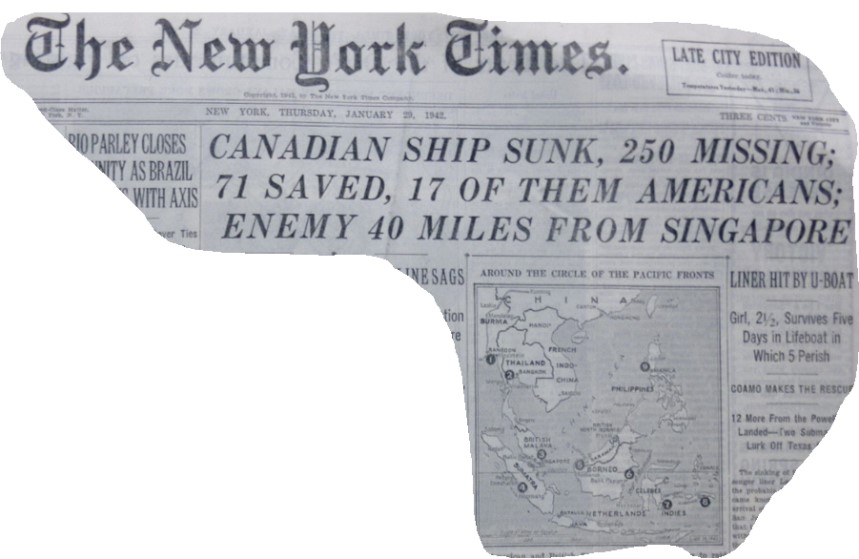

Weeks later, after first docking in New York, the survivors arrived home. Their rescue story had come to an end but not their nightmare. In reality it never would, but at least they were alive. For the families of the 251 children, women and men who perished when the Lady Hawkins was torpedoed by U-boat 66; their grief had just begun.

“a local hero recognized”

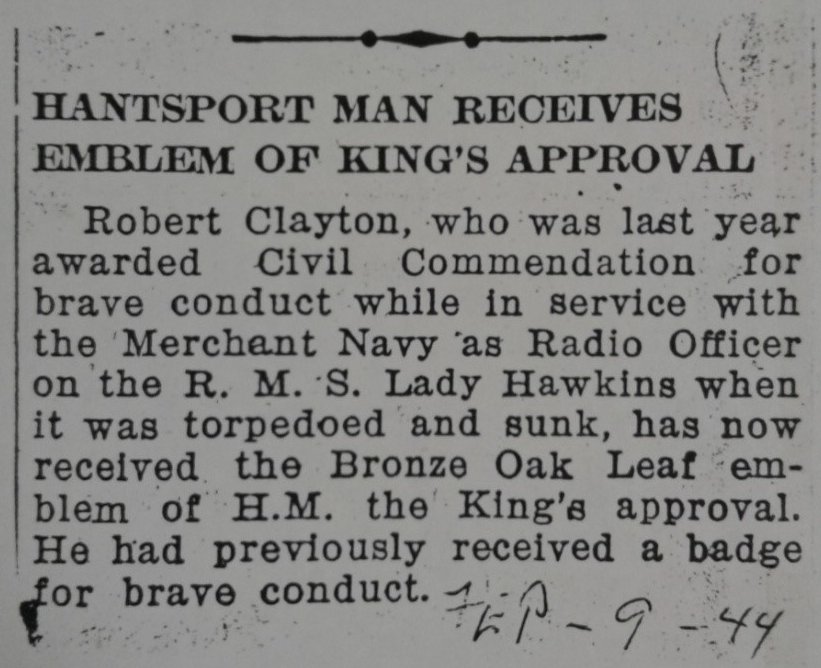

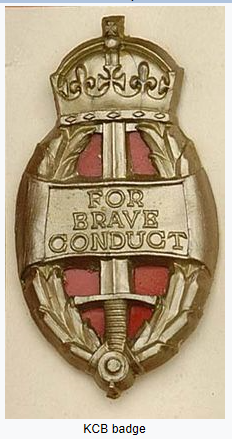

Robert Carter Clayton received two recognitions for his role that night. In December, 1943 he received a badge: The King’s Commendation for Brave Conduct. Later he was awarded the Bronze Oak Leaf emblem of His Majesty, the King’s Approval. Perhaps, an honour more meaningful to Bob Clayton was a recognition years later by Marion Parkinson. She was the missionary whose husband perished in the icy Atlantic. She contacted Clayton and asked if he would attend a conference where she would be speaking in Halifax. From the podium Mrs. Parkinson paid tribute to his heroic actions on that terrifying night in January, 1942.

Bob Clayton left the merchant marine following the sinking of the Lady Hawkins to work in the Halifax dockyard. Most of his time was spent on McNabs Island at the “sound range” working for the Department of National Defence as a civilian employee in the department of Research Establishment Atlantic. He also worked several years travelling the Maritimes as a repair technician fixing projectors in movie theatres.

Bob and his sweetheart Doris were married on June 19th, 1943 in the Ells family home. The Clayton home, 22 Willow St., is a hundred meters up the street. The sunroom on the front, where Bob spent many hours soaking up the sun’s rays, is a reminder of his struggle with TB. Those rays of sunshine produced vitamin D which was considered to be helpful for persons fighting tuberculosis. The disease had compromised his lungs and the fuel oil ingested at the time of the sinking caused further damage.

He and Doris lived an active live in Halifax until their passing. They never had children but enjoyed time spent with their numerous nieces and nephews. Many of them remember their uncle as a man who had a passion for electronics, constructing appliances rather than buying them. Bob used his skills as a licensed ham radio operator to relay information to the Atlantic Weather Network. Many local families appreciated his willingness to connect them via ham radio with other family who were in remote areas of the Canadian north where there were no telephones. The Claytons were outdoor enthusiasts who enjoyed boating and camping. They were, as well, dedicated members of their church. Around the age of seventy Bob Clayton received news he had developed liver cancer with little hope for recovery. His response was not what many expected. He is reported to have accepted his fate saying: “I should have died many years ago.”

Webster’s dictionary defines a hero as a person who is admired for great or brave acts or fine qualities. Robert “Bob” Carter Clayton fits that definition. He is but one of many heroes who are unknown in their own communities.

It took fifty-five years before the Canadian Government recognized the sacrifices of the 18,000 men and women of the merchant marine; 1,500 of them who paid the ultimate sacrifice. The Lady Hawkins was one of seventy-two Canadian vessels lost in WW2. Only two of the five “Lady” ships survived. In the year 2000, the mariners each received $20,000 in compensation for their service in the war effort.

Acknowledgements:

The author would like to thank members of the Clayton and Ells family for their contributions, especially Kathrin Grace, Doris’ niece. Appreciation is also extended to David Gillis, a fellow DND civilian employee.

Other information was taken from the Montreal Gazette, Feb. 2007 edition, Legion magazine, and Trident magazine.