Captain Fred Whitney Folker

A quaint home, owned by a former sea captain, stands on Avon Street in Hantsport overlooking the river. It is situated halfway between the former shipyards of J.B. North and Ezra Churchill & Sons.

Years ago the captain added a room to the house resembling a ship’s cabin. Through the porthole, and using a little imagination, one can see the barque Stadacona sailing on the incoming tide to Windsor. Watching from the riverbank is a woman. The captain of the ship, with his son by his side, is waving to his wife as the vessel passes their home.

The imagery is actually more truth than fiction. Captain William Folker took his youngest son Fred with him on numerous voyages aboard the Stadacona in the mid 1890’s.

It could be stated that William and Almira Folker’s son cut his nautical teeth on the belaying pins and spars of his father’s barque. And, like his father, his life at sea was eventually filled with astonishing stories and remarkable achievements.

Frederick Whitney Folker was born on April 21st, 1879, the youngest of the six children of Captain William and Almira (Parker) Folker. He grew up in a family that epitomized “those who went down to the sea in ships”. His grandfather Thomas Parker and his father were both master mariners. He had one brother who was a captain, two brothers who worked in the shipyards and two sisters who married captains.

Unlike his father, Fred Folker wasn’t able to fulfill his seaman’s certificates in waters of the British Empire. The “Golden Age of Sail” had come to an end. Vessels made of wood, trimmed with canvas sails and powered by wind, had been replaced by steel hulled ships with paddle wheels or screw propellers powered by steam engines. These changes required Fred Folker to leave Hantsport in order to attain certification in the larger and faster ships of the twentieth century. Certification requirements had changed as well with each rank needing not only knowledge of the position but also specific years of experience.

Folker moved to New York where years later he fell in love with Grace Louise Meyer, a German immigrant who met Folker while sailing as a passenger on his ship. They married in Manhattan on July 18th, 1928. Unlike his parents who married very young, Fred and Grace were ages fifty and forty respectively. Together they had one son, Fred Whitney Jr.

After sailing a few years in Canadian, American and South American waters, Fred Folker gained employment with the New York & Porto Rico Steamship Line. His first position was Quartermaster on the S.S. Mae. At age twenty-one it was obvious he was destined to become one of their elite officers. Captain Henry McDonnell, a Master with the company commended Folker, who was serving as McDonnell’s First Officer at that time. In a memo to the owners he remarked that Folker was “a sober, smart and intelligent young man — a trustworthy officer.” That was the type of officer companies in the passenger line business needed. The shipping company did regular eleven day cruises to the Caribbean carrying both passengers and cargo.

Fred Folker attained his captain’s certificate at the age of twenty-eight and first took command of the S.S. Vasco. His thirty-two year career with the New York & Porto Rico Line saw him serve as Master of the Santurce, Vasco, Borinquen, Carolina, Ponce, Brazos, San Juan, San Lorenzo and Coamo. The latter two ships were the finest of the Line’s ships. Folker commanded both of these vessels, spending the last eight years of his career as Master of the S.S. Coamo. Under Folker’s command the Coamo never failed, not even a day, on its regular route. This was considered a remarkable feat in the annals of navigation and a feather in the caps of its commanding officer and crew.

In 1931 Captain Folker was installed as a member of the Marine Society of New York, a prestigious organization that, among other things, assisted destitute children of seamen. He retired in 1939 after forty years at sea and returned to Hantsport. In his files is a letter addressed to him dated July 10th, 1939 signed by twenty officers who: “considered it a privilege and a pleasure to have served under your command.” Unfortunately his retirement was short-lived. Captain Fred Folker died in Hantsport on April 24th, 1943 at the age of 64.

On Board the S.S. Santurce

The newspaper headlines from May 4th, 1910 make for intriguing reading. The interesting aspect of those newspaper accounts was how differently they interpreted a wireless radio message sent by Captain Cates of the oil tanker S.S. Ligonier. The captain had reported a collision between his ship and the S.S. Santurce, a freighter captained by Fred Folker. Wireless telegraphy was a relatively new form of communication in the Cape Cod region at that time and the Ligonier was the only one of the two ships equipped with the technology.

Captain Cates’ message to the shore station was brief. He reported the collision, stating his ship was crushed in the bow but not severely damaged; he had taken 17 crew members of the Santurce on board his ship. Captain Folker, the chief engineer, along with two engine room crew remained on board the Santurce with the hope of running her to shore. Cates also requested help for the Santurce and said he would “stand-by”. He maintained communication with Captain Folker by megaphone until the ships drifted too far apart.

Cates’ wireless message was picked up by the newspapers. Their columns the next day varied greatly on the incident. One paper indicated Folker’s deck crew deserted the sinking Santurce, jumping on board the Ligonier while the two ships were lodged. Another story indicated Capt. Folker ordered all but his officers and engine room crew to abandon ship. Yet another account stated the Ligonier was missing and possibly had sunk with 45 persons aboard. Dozens of erroneous accounts of the collision appeared in papers across the United States. One can only imagine how the rumours grew and spread!

Folker, by then a captain for three years, played a heroic role in saving his crew and freighter that night following the collision with a ship twice the size of the Santurce. The S.S. Santurce had left Boston three days earlier after unloading a shipment of sugar from San Juan and was destined for New York. Shortly after 8 pm, in dense fog off Cape Cod, the Santurce was struck on the starboard bow by the S.S. Ligonier, a tanker carrying several hundred thousand gallons of oil. The lookout on the Santurce sounded the alarm shortly before the two ships collided; too late however for either captain to alter course. The collision tore a gapping 12 foot hole in the Santurce, part of which was below the waterline. Fortunately the damage to the Ligonier didn’t impact the oil compartments, preventing an environmental disaster.

However, the situation on the Santurce was grim. Water was pouring in the “after compartment” and flowing toward the boiler room. Folker ordered the immediate closure of the bulkheads in an attempt to keep the fire pit from flooding. Although water eventually reached the engine room it did not soak the furnaces as pumps were able to stay ahead of the incoming seawater. Folker ordered “full steam ahead”. He and another officer stood at the bow as the Santurce limped 20 miles around the Cape, in the pea soup fog, toward the beach in Provincetown. The ship’s bow was high in the air and the wake of her screw washed over the taffrail (rail at stern). There was fear that the waterlogged ship’s bulkheads might fail, taking the Santruce to the ocean bottom within minutes.

At dawn Folker was able to breathe a sigh of relief when the Santurce was beached in Provincetown proving his former commanding officer correct in that Fred Folker was indeed “a sober, smart and intelligent young man — a trustworthy officer.”

On Board the S.S. Coamo

It was during the mid 1930’s when the President of the Dominican Republic, Rafael L. Trujillo, was modernizing his country that Captain Folker gained much fame, particularly among ship’s officers who sailed the Caribbean. One project which would improve the economy and bring prosperity to Trujillo City (present day Santo Domingo), the county’s capital, was to dredge the Ozama River and inner harbour, thus permitting large ships direct access to the city. The Ozama river was made prominent by Christopher Columbus who navigated the waterway in December of 1492 on board the Santa Maria.

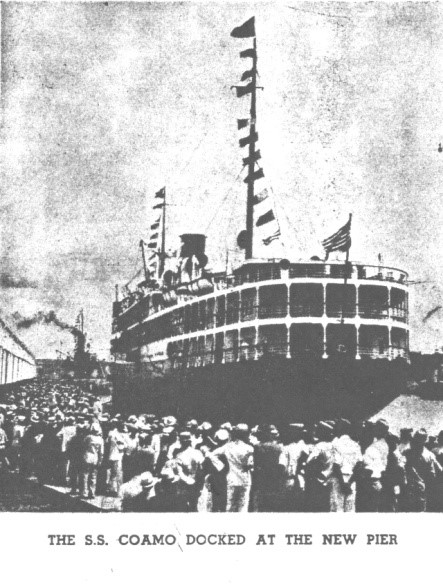

With a new pier constructed, President Trujillo eagerly awaited a shipping line that would risk the untried channel. Realizing the tourist benefit and economic spinoff for both the country and the New York & Puerto Rico Line, Captain Folker was asked to take the risk. If successful, it would eliminate the costly measure of shuttling cargo and passengers in smaller boats to the capital, a labour intensive and time consuming task. In addition to cargo, the Coamo could carry 350 passengers.

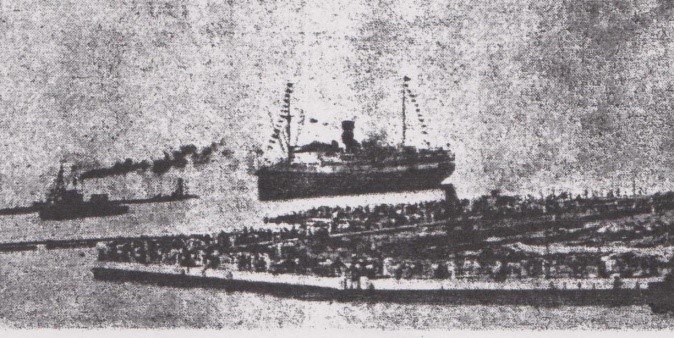

On August 18th, 1936, with President Trujillo viewing the much awaited passing of the ship from the vantage point of Fort Ozama, Captain Folker and his crew skillfully manoeuvred the 7,057 ton S.S. Coamo up the river and into the inner harbour. Their sense of accomplishment and pride must have been bolstered when they received a twenty-one gun salute from the fortress.

Fort Ozama, coincidently, was the very spot Columbus landed over four hundred years earlier.

Being 429 feet long, 60 feet wide and requiring a draft of 24 feet, the Coamo far surpassed the size of any previous ship on the river. Joining the President for the viewing were business leaders from America, eager for commercial prospects if this venture was successful. As the Coamo finally gained entrance to the city harbour and made its way to the pier, over twenty thousand jubilant residents cheered its arrival. Dominican and American flags flew everywhere.

“I felt like a modern Columbus” the captain later told those who greeted him dockside. “I could not help but contrast our tremendous reception, which symbolized the opening of the new canal with the landing of that first great navigator.” Captain Fred Folker and his crew had definitely demonstrated the safety of the new channel and harbour. What earlier was an impossible feat now opened the Port of Trujillo for business. “The new facilities”, the captain stated, “would make ship entry, loading and unloading, as simple as in New York.” The captain was hailed as a hero by the Dominican government. The master’s response: “My men were the heroes of the day.”

Almost two years to the day after that historic event, the Council of the Order of Merit – Juan Pablo Duarte issued the following Decree (#2409); “By virtue of the authority of the National Congress of May 26, 1936, considering that Mr. F. W. Folker, Captain of the S.S. Coamo of the New York & Porto Rico Steamship Company was the first who, in a ship of large size entered the port of Trujillo City, thereby demonstrating the safety of that port which now contributes to the National prosperity. having heard the opinion of the council of the Order of Merit, Juan Pablo Duarte Decree conceding to Mr. F. W. Folker, Captain of the S. S. Coamo the decoration of the Order of Merit Juan Pablo Duarte in the grade of Knight. Given in Trujillo City, District of Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, the fifteenth day of August, 1938. Signed: Rafael L. Trujillo.”

An article published in October, 1938 noted: The commendation bestowed on Captain Fred Folker is one of the highest honours that can be conferred by the Dominican Republic for distinguished service to the nation. In bestowing the award to Captain Folker, the Dominican Government also took into consideration the Captain’s past acts in the interests of citizens of the Republic.

Note that the president’s photo is personally addressed to Captain Folker and signed, making it interesting to discover what past acts the captain had done for the republic.

Captain Folker was on vacation when the cable from Santo Domingo arrived at the headquarters of the New York & Porto Rico Steamship Lines. It read as follows: “Please advise Captain Folker he has been decorated with the Order of Juan Pablo Duarte of the Dominican Republic.” General Superintendent of the Steamship Line, B.C. Edwards, forwarded the cable to Folker while adding the following comment: “You may want to write to the president of Santo Domingo acknowledging this honour.” One might wonder if this was necessary advice, but considering a statement in the newspaper El Mundo written just prior to Captain Folker’s retirement the suggestion may have been warranted. The journalist, Jeorge Felix, stated the captain was “a modest man and timid to a certain extent.”

In the El Mundo retirement article Captain Folker spoke of his luck during his forty years at sea. Not once was he at sea in a hurricane. What he did not tell that journalist was his experience in a hurricane while docked in San Juan, Puerto Rico or of other major storms he encountered while in command of the S.S. San Lorenzo. Perhaps Jeorge Felix didn’t specifically ask the modest captain about that. Interviews with other newspapers give a glimpse as to the dangers Captain Folker encountered while sailing in the hurricane prone waters of the Caribbean.

Footnote regarding the S.S. Coamo. During WWII the Coamo was involved in the rescue of 75 passengers and crew off the HMS Lady Hawkins which had been sunk by German U-Boat 66. 250 lives were lost. One of those rescued was Hantsport mariner Robert Clayton. On Dec. 2nd, 1942 the S.S. Coamo was sunk by Germany U-Boat 604 with 186 lives lost.

On board the S.S. San Lorenzo

Barometer Falling

Hurricanes were not given names in that era but some bear the name of a special occasion such as the one Captain Folker experienced in San Juan on the day celebrating Saint Philip (San Felipe Segundo), September 13th, 1928. Early radio reports indicated a tropical storm was pending but the worst of it would pass by 80 miles south of Puerto Rico. At that time hurricane warnings were not as accurate as today nor were they even available to many inhabitants of the Caribbean Islands.

Folker became alarmed when the barometric pressure dropped from 29.5 to 28.85 inches in just three hours; a phenomenon he had not seen before. He immediately took measures to secure the San Lorenzo. It was an “all hands on deck” situation. Twenty–two hawsers (mooring lines) were put in place as the category five hurricane with 260 km/h (160 mph) winds began to pummel the island. Folker later said he (had) ”never seen anything like the fury of that hurricane. The air was filled with flying objects and rain fell with the force of hailstones in the abundance of a waterfall.” For twenty-four hours his crew along with every male passenger on board weathered the severity of the storm. It was critical that the hawsers stayed tight to prevent the wave action from pounding the ship against the pier. As lines snapped a dozen men leapt into action to replace them. From 2 am to 3 pm they watched as massive waves tossed smaller boats high onto the shore and the wind ripped roofs off pier sheds. Some ships were swept out to sea while others were dashed against the rocks. Folker’s exhausted crew and passengers somehow managed to keep the San Lorenzo tight against the pier. None had a moment’s rest in twenty-four hours!

When the fury of that hurricane passed Puerto Rico, the other islands and the southern coast of the United States, the death toll and damage was the worst ever recorded to that date. 4000 lives were lost; almost 25,000 homes destroyed and another 192,000 damaged. 500,000 people were left homeless. The estimated loss in today’s figures was over $1.5 billion.

Captain Fred Folker’s decisive action saved his ship, crew and those passengers who were still on board but now he was faced with a new dilemma. The city of San Juan was basically destroyed; debris, downed trees and power lines made travel and communication impossible. Over one hundred passengers were to have boarded the San Lorenzo for the return trip to New York. It became apparent to Folker that chaos would follow as islanders faced shortages of food, water and shelter.

With the realization that the 100 passengers who had made reservations could not possibly reach the port, Folker made the decision to weigh anchor. Luckily he did as in the ensuing days riots broke out all over the island. No doubt the safety of his passengers, his crew and his ship were foremost in his decision making. The food supplies on the San Lorenzo would surely have been a target of the looters.

Captain Folker may indeed have been lucky to have never experienced a hurricane while at sea and likely, after his experience of the San Felipe Segundo hurricane, would he ever want to experience one. He did however, from time to time, face angry seas during those cruises from New York to the West Indies. On one occasion he recalled “the grand piano plunged about the dance floor until it resembled kindling wood more than it did a piano”.

A keepsake letter found in Captain Fred Folker’s files gives wonderful testimony as to why he was so highly respected by a president, his superiors, his fellow officers and his passengers. The letter, penned by passenger C.M. Britten of New York on February 3rd, 1933 was sent to Folker after what must have been a harrowing and distressing cruise aboard the S. S. Coamo; a trip that took two extra days.

“Capt. Folker’s ceaseless thought for the passengers included frequent visiting to the sick, cheering words to the uncomfortable and the exhibition of patience that seemed almost inhuman for he was beset on all sides with frantic and fearful inquiries. When one realizes that this happened in the face of physical discomfort to himself when seas practically swamped his own cabin, it leaves one with the impression that selfishness is not everywhere.”

The article written by Jeorge Felix when Folker retired referred to the captain as being a timid and modest man. Modest — yes. Timid; likely not! Perhaps Mr. Fleix made a similar misrepresentation of the captain’s character as did the journalists who misrepresented the facts about the collision incident in May of 1910. Those that served under Fred Folker’s command; having experienced his skillful handling of stressful situations would never have thought of their commander as being timid. They would have likely agreed that Captain Fred Whitney Folker was a wise, unselfish, caring and empathic human being.

The author extends appreciation to the Folker family for the use of news clippings, photos and personal stories of Capt. Fred Folker.