In her remarkable 2001 book “invisible shadows : a Black woman’s life in Nova Scotia”, the late Verna (States) Thomas writes about her experiences growing up in Mount Denson, leaving home and moving to Preston where she later married and raised a family, and also her awakening to the experiences of other Black Nova Scotians; “how they climbed out of the bondage of slavery, isloation, exploitation, and neglect and what effect that process continues to have on those who live in the province today”. 1

Col. Henry Denny Denson

Mount Denson was named for the manor built by Colonel Henry Denny Denson. Born about 1715 in Ireland he was in Nova Scotia by 1760 receiving a grant for 2000 acres and bought an additional 2250 acres making him one of Falmouth Township’s largest landowners. “Denson realized a substantial income through the breeding and raising of livestock. He was a militia officer from the founding of Falmouth and road commissioner and collector of impost and customs. In 1773 he served as acting speaker of the Assembly at Halifax.”2 He was also a slave owner.

It was said that he was very strict. Colonel Denson supposedly asked his slaves to bury him in an upright position when he died so that he could continue to watch over them. But, as the story goes, they did not follow those orders. They were worried he would come back to life after they noticed his forehead breaking into a sweat three days after his death, so they buried him in the typical manner and placed 10 feet of soil and rocks on top of his grave.

In 1770, the Falmouth census showed a total of 22 people living in his household. 16 of these people were enslaved and from the United States. At the time of Colonel Denson’s death in 1780 there were at least 5 enslaved people in the household. Jube, Phebe, Pompey, Spruce, and John were the names of enslaved people sold from his estate.

Capt. Abel Michener

Capt. Abel Michener born in Rhode Island and land owner in Falmouth Township was also a slave owner. In May 1781 he had an advertisment printed in the Nova Scotia Gazette offering a £5 reward for the return of a “run away Negro Man, named James”.3

One source states that even after the Slavery Abolition Act came into effect in the British Empire on August 1st, 1834, the slaves “stayed with the Michener family because of how kind they were to them”. In fact, only children aged six and under were freed by the act in 1834. Everyone else had to work without pay as apprentices for the next six years. The British parliament paid £20 million to slave owners in over 40,000 awards to compensate them for the loss of “their property.” 4 No restitution was paid to former slaves, many of whom were forced by circumstance to work long afterward as indentured servants.

Col. William Henry Shey

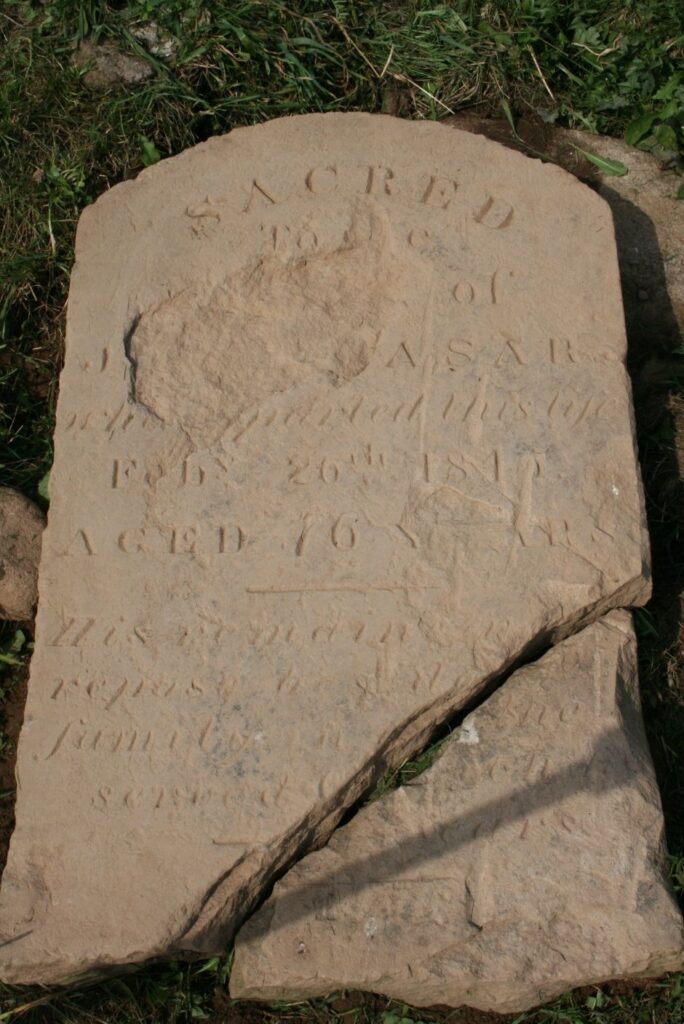

Col. William Henry Shey (1769-1854) resided at Green Grove Farm, Falmouth Township. “An article entitled ‘Old Time Reminiscences’ appeared in a 1911 Windsor newspaper and included the following: The writer remembers well when Col. Wm. Shey owned and occupied the above mentioned property, together with the buildings which were kept in fine shape. Juba Caesar was a coloured slave brought here by old Mr. Shey and at his death came into posession of Col. Shey. Juba was a faithful servant, and when he died Col. Shey had his remains placed in the family lot. The writer has often been told by his parents and grandparents of Juba. He had a gift of relating the reminiscences of his life and one special topic was how very kind Massa Shey had been to him. One of his presents to him was a flock of sheep and Juba said ‘in dem dar sheeps war big money, and all dat Massa Shey axed for keeping dem dar sheeps was de wool and de lambs’.” 5,6

who departed this life Feby 26th 1845 Aged 76 Years” 7

Verna Irene (States) Thomas

Verna Irene (States) Thomas, “a Canadian woman of African, Irish, and Native descent” 1 was born on 30 May 1935 in Mount Denson, daughter of William Randolph States and Sarah Jane States.

In her 2001 book, invisible shadows, she describes life in Mount Denson before she was able to recognize racism. She spent her childhood picking berries in the summer and skating, skiing and sledding in the winter. She and her siblings did chores like empty the chamber pots, pick up the family mail from the post office, and run errands at Ainsley MacDonald’s grocery store. Some days they went into Hantsport to the L. B. Harvie grocery store, crossing the Halfway River aboiteau over a plank bridge. While on their way to run errands, her mother would always insist that she stop into her Grammy Becky’s house to see if she needed anything. “Aunt Becky” as she was known around Hantsport lived on Schurman Road in a little cabin.

Verna attended school in Mount Denson, a predominantly white community. She was involved in various clubs like the Junior Red Cross Group and Canadian Girls in Training (CGIT). She later states “during my school years I was never aware of a double standard for Black children though sometimes my exams and even everyday schoolwork appeared to be marked differently”. She was told by her parents that she would sometimes have to know twice as much as her classmates.

In her childhood, Verna’s brother was hit by a car, thrown into a ditch and died as a result. The police found the drunk driver later but when tried in court, he received only a brief time in jail.

Though they didn’t talk about racism, Verna’s mom still wanted to make sure that they maintained cultural ties, so the family attended the annual Windsor Plains coloured Sunday school picnic at Evangeline Beach in July.

When Verna was 14 years old she spent two weeks at her sister and brother-in-law’s house in Cherry Brook near Preston. Since she had never learnt about any Black communities in school, this was an overwhelming experience for her. After returning home, she contemplated how growing up in a protective family had made her “immature concerning racial differences”.

When Verna got a bit older, she was given more responsibilities around the house, like sewing, cleaning and taking care of her younger siblings. She thought this was partly due to her parents not wanting her to socialize with white people which they worried would have led to her being in a mixed relationship. They disapproved of this because they wanted her to keep her culture. “People should marry their own kind” is what her parents would say. These further restrictions pushed her to moving out of her parents’ house to the Preston area, where she would work at her brother-in-law’s store in Cherry Brook in 1953. This is where Verna started to encounter racism first hand.

In one instance, Verna was walking home from a ball game with a group of other Black women when a police officer drove up beside them. The officer asked them if they knew where a specific person lived. Everyone else was quiet but Verna said “no”. The officer told her she was lying because everyone knows everyone in this community, so she said that she had just moved there. He told her to get going because if he got her in the car “then she’d know something”. The girls were afraid, and all left. They then told Verna that she was crazy to talk to an officer like that, and that “you don’t talk to white people”. This led to Verna realizing that race had to do with how people were treated. While talking to other community members, everyone agreed that the police took every opportunity to arrest people to demonstrate their power and authority.

She applied for a job at Moirs’ Candy Factory in Halifax, where she was told they didn’t hire “coloured people”. She applied for a job at the Metropolitan store, where she was told that they weren’t hiring even though there was a “help wanted” sign up. Black people also weren’t permitted in establishments like the hair salons where there were white people or to sit in the main section of movie theatres.

Eventually, Verna took jobs doing domestic work for white women. One asked Verna to do the equivalent of three days’ work in one day and was paid $2.50. Around this time, Verna had been reading about Rosa Parks, the Bus Boycott, and the Civil Rights Movement. When the woman asked her to clean the ashes out of the fireplace, along with all her other usual tasks, Verna bravely told her that she wouldn’t be her slave and quit.

before our marriage.” 1

Verna married John Edward Thomas and raised seven children while finishing high school, taking university courses, and persuing a career.

“She was a coordinator with Halifax Metro Welfare Rights and a human service worker with The Black United Front of Nova Scotia. Verna was involved with various church, social and political organizations and committees. She was a long-time member of East Preston Baptist Church. She was a past First Vice-president of the National Antipoverty Organization, Charter President of the East Preston Women’s Missionary Society and Charter President of Preston Area Learning Skills Program, Charter Board Member of East Preston Recreation Centre, and Charter President of East Preston PC Women’s Association. Verna was a humanitarian at heart, her work and community involvement focused on issues that supported and aided in the equitable rights and dignity of all people. Verna took great satisfaction in knowing that she was a part of a continuum, picking up where a past generation has left off. It was her hope that this generation would pick up from where she left off.” 8

Sources:

- Thomas, Verna invisible shadows: A Black Woman’s Life in Nova Scotia. Halifax, N.S.: Nimbus, 2001.

- J. M. Bumsted, “DENSON, HENRY DENNY”, in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed August 1, 2021.

- Nova Scotia Archives, Nova Scotia Gazette 22 May 1781 page 3 (microfilm 8159)

- Natasha L. Henry, “Slavery Abolition Act, 1833“, in The Canadian Encyclopedia, published online 2014/5, accessed August 1, 2021.

- Duncanson, John V. Falmouth : A New England Township in Nova Scotia. Belleville, ON: Mika Publishing Company, 1983.

- States, David W., “Presence and Perseverance: Blacks in Hants County, Nova Scotia, 1871-1914” Masters of Arts Thesis, St. Mary’s University, 2002.

- Hantsport & Area Historical Society, Shey Family Burial Grounds – Field Trip, 27 September 2017.

- Obituary of Verna Thomas, Chronicle Herald (Halifax N.S.) 31 August 2005.

- Robertson, Allen B. Tide & TIMBER: HANTSPORT, Nova Scotia, 1795-1995. Hantsport, NS: Lancelot Press, 1996.

- Riley, L. J. History of Mount Denson, 1959.