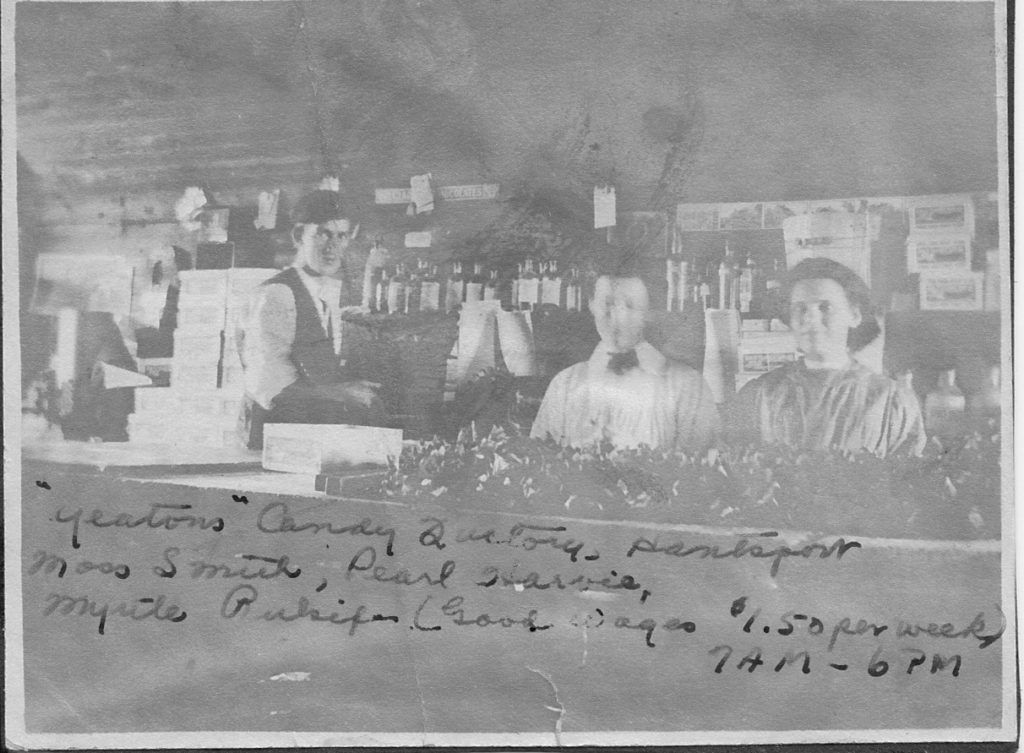

Taped Interviews with Maurice “Moss” Smith

Hantsport, NS – Summer 1975

OFY Project – Historical Insights

CANDY MAKING:

In 1895 an old gent arrived in town by the name of George H. Yeaton. He had worked for the Halifax Baking Company, and he got an idea – – the sales of candy. He thought he’d like to start a little candy manufacturing company. His wife happened to be from Hantsport and they’d come here a lot and lived here. They say he started with about fifty cents worth of sugar. The first batch of candy he made cost that much. Then he made a few other things. He wasn’t a candy maker but he employed a candy maker from Halifax, from Moirs, by the name of Beazley.

He started manufacturing in a long building (they called that Station Street) and on the further end of it was a grocery store operated by George Davision, and up this end, the Davision family lived. In the other end lived a family by the name of Pulsifer, I believe.

He got making a little more and a little more and by and by he had to have the store. They gave up the grocery business there, he took that over and then he took over the part of the building this way and made rooms there and the lower part was the chocolate room, upstairs over the store was a hard candy room, and the room out in the back was the old Band Room, the Hantsport Band used it to practice in it.

Well, he got stoves and little machines and he kept building. It got to 1900 and it was getting to be quite a little thing. He went out and sold candy around and took orders and delivered orders. They had two or three working for him then. They were only using marble to cool it on. In 1905 they put the water works through here. In April they started. Delancy Faulkner was mayor at the time and I was at the first turning of the sod the first of April. They had to go nine miles to the lake to build the reservoir on this end of it.

Well, I went to work there (the candy factory), I was only 14 in 1905. I started this day and they were cooling the candy on marble and I was just standing around. I didn’t know anything much about anything. I maybe handed them something, weighed out a pound or two of sugar, you know, do little odds and ends. I was standing by the cooler, heard a rushing noise and it was the water coming in the cooler — the first water from the Hantsport water system to go in the Yeaton’s Candy Factory.

Well, it was coming on Christmas, this was around October, so we moved everything more or less near where the water was flowing under the coolers – – a steel slab, was like a basin with a bottom of it just touching the water and running to keep it cool. We moved all our molds over to one cooler and used the other coolers to cool our batches of hard candy. I was just a helper. In four months, I was making candy myself. I think I was quite a planner, learner, and was a strong little fellow.

We’d make that year about two or three ton a week of candy. It got up to, oh maybe five times that as the years went on. Well, then they enlarged and put in a cream room, made fondant cream for centers for chocolates. They used to mix that by hand, then they had a cream beater. It was a big bowl machine with big ploughs that would turn over the batch of candy, about sixty pounds of fondant cream at one time. Put it on the stove. Then it was taken out and put in a barrel and they got molds of starch – – it was like a printing press: shove in the boards with the different molds on it, pull a lever down, that would leave an imprint where we’d run the cream in these molds with a runner (running stick and a funnel). When that got set we sent it down to the chocolate room. We got up to twelve or fifteen girls rolling chocolate after a time.

It went on for three years like that. We made every king of candy but marshmallow and gumdrops. We made everything else. Sometimes we’d have as many as seventy-three different kinds of penny pieces. Today, there isn’t any; you can’t buy them. Lots of caramels, made all kinds of coconut stuff, and peanut clusters, almond dip, walnut dip.

It was very interesting, but in some ways I didn’t like it, but I kept going. It got a little monotonous – – I was as far as I’d ever go. Then I had another thought…the first was started and I went into that and was away from there nearly four years. Then when I came back home again I had a different outlook into working; that was quieter, not so much shell fire and all that. I was a little more settled. I had gotten married in 1913.

They sold candy all over western Nova Scotia, eastern Nova Scotia, had a good sale in Cape Breton Island, they sold lots there, and over on P.E.I.

This Beazley, he stayed on as foreman till up about 1914, and he went to Winnipeg and he came back, the war was on then, and he took over as foreman again. He took it over from another fellow O’Brien. He worked there for two years. After I came back they put me in his place and let him go. He was quite a candy maker.

I learned all mine first hand. I took it as a little lab, that little candy business. We could make things that bigger places would like to have, like flavors. A traveller from Willard Chocolate Bar Company in Toronto came to me and wanted to know if I’d give him a recipe of the Coco-Venus caramels we made. I said, “Yes.” He said, “I’ll pay you.” I said, “No.” He said, “Why won’t I pay you?” I said, “I know you won’t make them.” “Damn sure I will if you give me the recipe.”

“Oh, I’m gonna give you the recipe, but you’re not gonna make them.” “Well, there’s no sense in saying that.”

So he came back about three months later. I said, “Did you bring back some of those caramels?” He said, “You didn’t give us the recipe.” I said, “Look, I’ve only got one question for you. What do you use? What do you cook by, steam or flame?”

“Well, steam, of course, it’s up-to-date.”

“Well, those are to be made with flame.” See, the condensed milk in the batch stirred by hand, that milk just scorched a little, made a lovey brown and made a lovely taste. It was a lovely caramel. We mad tons of it.

But the best piece of candy of all I ever ate, in a chocolate, I made myself, my own recipe:

Fruit and Nut Caramel

10 lbs. Sugar, 10 lbs. Glucose, about 2 lbs. of nucro butter and about 2 qts. of condensed milk and some creamery butter, unsalted. Put the salt in after it’s cooked. You mustn’t put salt in anything you’re making on the flame. It doesn’t taste good. It spoils the taste.

Well then, you cook that up to 250 deg., take it off the stove and out 10 lbs. of fondant cream in it and stir that all up. Then you put about 7 lbs. of coconut in it, about 4 lbs. of raisins, 4 lbs. of walnuts, flavor with vanilla, pour it along the marble, roll it flat three quarters inch, mark it in the size of caramels and cut it up in little squares and send it down to the chocolate room to the girls to cover it with chocolate.

There used to be a minister come over from Kennetcook, bring people over here when I was making candy. He says, “Here’s the man who says it’s simple, that everything is simple.” One fellow says, “Well, perhaps he’s right. We’ll see what he does.”

Simple to me, yes; not to them.

These batches would be 310-320 degrees. There was a lady came in one night. There was a batch of hard candy on the hook, just starting it. She said, “Let me pull that. There’s nothing to that.” I said, “Sure. You think you can?” “Yeah, there’s nothing to that.” So I let her pull it. I didn’t give it to her when it was real hot because I started it. Oh, I could pull that out about the length of this room here and just give it a flip over the hook and catch it again, and it would crash together. Ruth Freeman, it was Dave Freeman’s first wife, came in the next morning and said, “Look what you’ve done.”

“I didn’t do that.” (All blisters on her fingers.)

“Well”, I said, “you said it’s easy; isn’t it?” “When you did it.”

Oh, it was fun, you know, it was so simple.

We made a lot of kisses. Our best kisses was a molasses kiss, and there was a candy maker by the name of Smith – – he gave me the hint on how to make it good.

Never cook your molasses. Cook your batch till about 280 deg., pour enough molasses in to bring it back to 257 deg., pour it on the cooler, turn it in, turn it in till you get it so you can put it on the hook and give it a good pulling, wrap it. There’s your kisses. Simple.

We made after-dinner mints, peppermint drops and love drops. Now, love drops was the simplest kind of candy there was. It’s just sugar, water with a little wee bit of glucose, cooked up to 250 deg. Take it off the stove and drain it on the side of the kettle and into the mold – – don’t pour it in; run it in with a runner. When you release the little stick, that allows so much to come out. Fill the mold. It was quite a thing you know. There’s some good and some poor runners. Oh, you got to be, after a while, quite a good artist.

We’d make grocer’s mixtures and we put a few batches of these (love drops) through it to help –some people thought they were creams. It was good stuff to eat, though, cheap.

Our busy season was in the fall, but after Christmas we used to make all the fruit syrup. We’d make 2 or 3,000 dozens of those, quart bottles. Sold a lot to the fishermen in Lunenburg and they went to the Banks. The water would be bad and they’d pour that in their barrels with the water to give it a better taste. Oh, we sold a lot of fruit syrup.

Then we made peanut brittle and all that stuff.

Sponge taffy: 13 lbs. sugar, 7 lbs. glucose, cook it up to 300 deg., a drinking glass of soda and mix it up, pour it in and stir it fast and pour it on the board. You cut it up with a hand saw and saw it in squares.

There was nothing to that, but the simplest candy to me was peanut brittle, but most everybody will put in soda, but soda spoils it for me. Reason I think the big fellow is putting soda in – he make’s a cloud, he’s hiding what isn’t there, what should be there – peanuts. He’d only put about half the amount of peanuts. This soda would make it all cloudy and there wouldn’t be half the peanuts, but I put so many peanuts in you could see the peanuts. Peanuts were very cheap in those days. Raw peanuts for brittle were sold sometimes for three or four cents a pound. Oh, sometimes they’d vary. They’d come from Java, China; the Java peanuts were good. But pretty well everything we could get around here.

They’d make marichino cherries. How do you get the centers in the marichino cherries? Well, you make a batch of fondant cream, it’s a little lighter than ordinary cream, this is for cherries. You heat it and you dip it, have a little wire stick to put the cherry on and you dip it, put it on paper and let it cool. Send it to the girls and they’d roll it. They had to be rolled about twice. After those things got about two weeks old, that fondant cream would start to melt a little. When you eat a marichino cherry, there’s always a little juice in there and that’s it, it’s a good cherry. That’s manufactured right.

The girls, there’d be two girls at a table and they’d have a big tin of chocolate there, melted. They’d take some out and put it on the marble and then beat it with one hand till it got cool enough, then they’d grab this maraschino cherry, put it on a paper and make a string on it (with chocolate). See how simple it is?

Well, I’ll tell you who was one of the best rollers, Mary Tracey up here. Beatrice Pelrine, Evelyn Amiriault, there was quite a few. Now those girls are all still living. It must have been good healthy work. There was about twelve of them, Pauline Tracey, Mrs. Stan Taylor (she didn’t roll much, she packed), another Green girl, a Bezanson girl, oh, several others.

We had a kiss wrapper that would wrap 150 to the minute. You’d get the batch of kisses all made, pulled, and put them on the board and start the machine, have the paper there, thread the place with the paper, it would be square, but that cut the kiss off and there would be two little things shoot out and grab that and shove it into the paper and it would go down the wheel and come to these two things on the end that would twist the ends. Put a little tin down under the spout and it would be full of kisses.

There was one girl who cleaned the machine and looked after it and she got to be the girl on that machine. She rolled chocolates, Mrs. Ken Weagle. See, a lot of it isn’t history in a way. But they never used that machine much after I quit. Mr. Johnston (the new owner) sold it. He didn’t have Mrs. Weagle to operate the machine or me to back her up. Oh, she was quite a person. They were good girls. There was about 25 of us all together, that counted office staff and truck drivers, shippers, travellers. It was quite a little thing.

We never made much for Easter, we made a few Easter kisses, more or less. These other things, they ran into Easter. It’s seasonal.

Humbug – it’s a funny piece of candy. Well, you’ve seen them, peppermint humbug. They make them different today. They used to be four cornered, cut just opposite. All they are now is just a cushion. Simpler. I liked the other way.

If a man wanted a barrel of grocery mixture, we’d put his name in a stick of candy, his name right across it. We’d just make the letters, wrap it up in a piece of candy, pull it out flat and cut it up and it would go through the mixture. Oh, I’ve made it for O’Brien, different fellows along the South Shore. We’d make “Merry Christmas” in some, a strawberry, a swastika, a Maltese Cross, sometime a flag. That’s all gone. You don’t see any of that today. There wouldn’t be a fellow around able to do it now.

When jazz garters first came out we would make all the stripes, you know, and I’d ask some girl there, “Let me see your garter you’ve got on.” I’d copy those stripes. Oh yes, I think they’d get the gaudiest garters they could so they’d try to puzzle me to get the colors in it. You see, you make a big white batch first, you color several different pieces, green, pink, red and brown and you fix them all up on the board. Then when you brought out your main batch, you shook it up, then you put all these little things out and it made these long stripes on the big batch. Then when you started pulling, it out, it would all come with it and you would have all these different colors. Then when we’d make the rosettes, make them round, you know. It seems to be all bulk methods. Oh, they’d make some ribbon, I guess. The best clear toy was made of sugar and cream of tartar, and they were cooked up to 300 degrees. Once they cooked more, they turned too dark. They had to watch that. Had to be very careful. Had to oil the molds, we’d use olive oil or salad oil.

We’d make all kinds of kisses, coconut, pineapple, orange, lemon, spearmint. In the summer, we’d have to have the coolers for the girls with the chocolate machines and they’d get the ice from the old brick yard pond, down by the North shipyard.

We used to skate there all winter and the fellows spit on it and all, and then we’d gather it up and put it in the coolers to cool the chocolates, you know, and they stored it in the old jail back of the station. Well, the last years we used it as an ice house, and it had two windows with iron bars on it.

Oh, I was just as big a little devil as ever lived in Hantsport. I always had a way I got clear. I was quite a planner, an instigator, but I never got caught. I was a lovely little fellow, by all the ones who used to find fault with the boys. They used to tell my mother that I was one of the best boys.

We used to have some awful times down there; an old fellow used to hang around the town – He’d go to some of his relatives, around the back door to get a feed. You wouldn’t let him in the house. He’d just have to eat on the steps. He used to live in the jail apartments. Yeah, there’d be four of us. Two of us would be bad and the other two would be good. I always wanted to be the good one. They’d go tease and upset him and he’d chase them up town and while he was gone, we’d upset all the rest. Well, you know it wasn’t smart at all, when you look back over it, because you know it was foolish. Same way when I went to school. I was half smart but I thought more of playing tricks on the teachers than on other stuff, and I was nearly forty years of age before I realized that I didn’t fool the teacher. I fooled myself.